“Research bridges the past with the present, using technology to reconnect us with lost knowledge and inspire future innovation.”

Research

Research has allowed me to bridge the past with the present through digital media. My projects focus on rebuilding historical sites and cultural practices, using technology to reconnect with lost knowledge and inspire societal change. This journey has taken me through various interdisciplinary collaborations, expanding the possibilities of virtual reconstructions and digital heritage preservation.

I've worked on several projects that merge technology with cultural heritage throughout my career. From reconstructing the Temple of Amun at El-Hibeh to representing the Huron-Wendat village in Longhouse 5.0, my work has aimed to create educational experiences that honour and preserve historical narratives. These projects have involved collaboration with experts in archaeology, anthropology, digital humanities, and computer science, ensuring the digital environments are accurate and culturally sensitive.

Despite the challenges, I always make time to pursue various research projects. These projects focus on rebuilding the past to reconnect with lost knowledge, particularly those that can inspire positive societal change.

I’ll work through this section chronologically, beginning with my Master’s Research Project.

El-hibeh Reconstruction Project

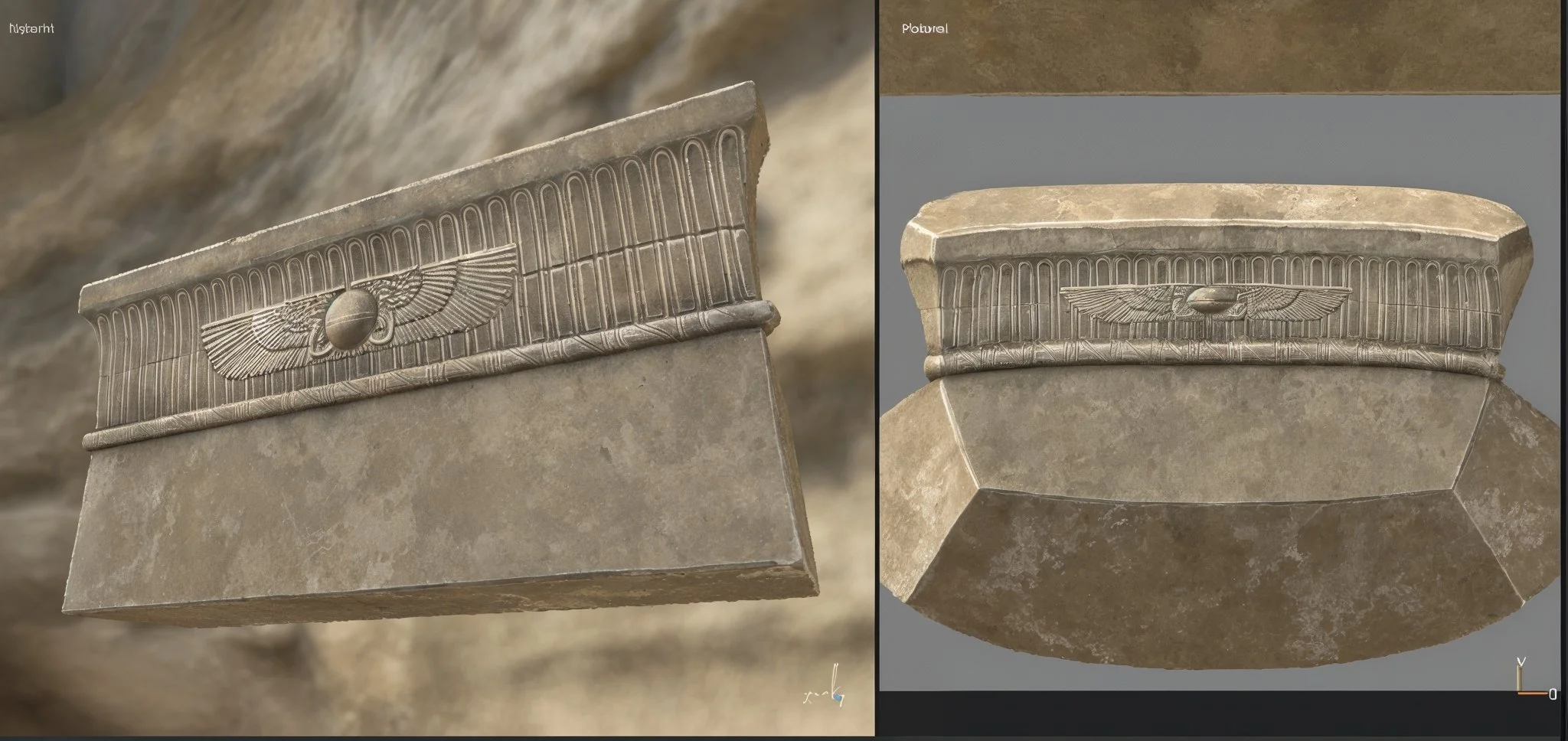

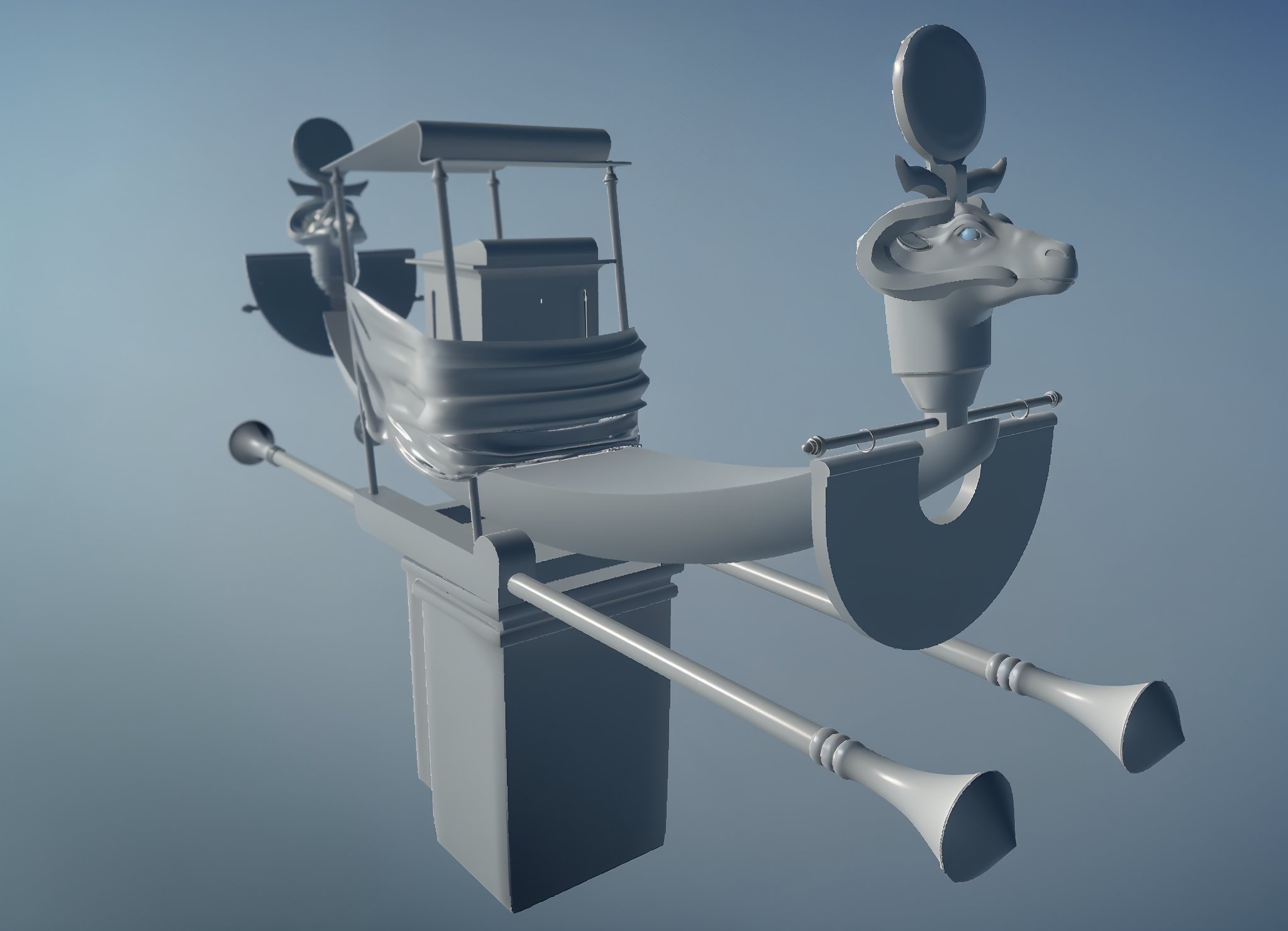

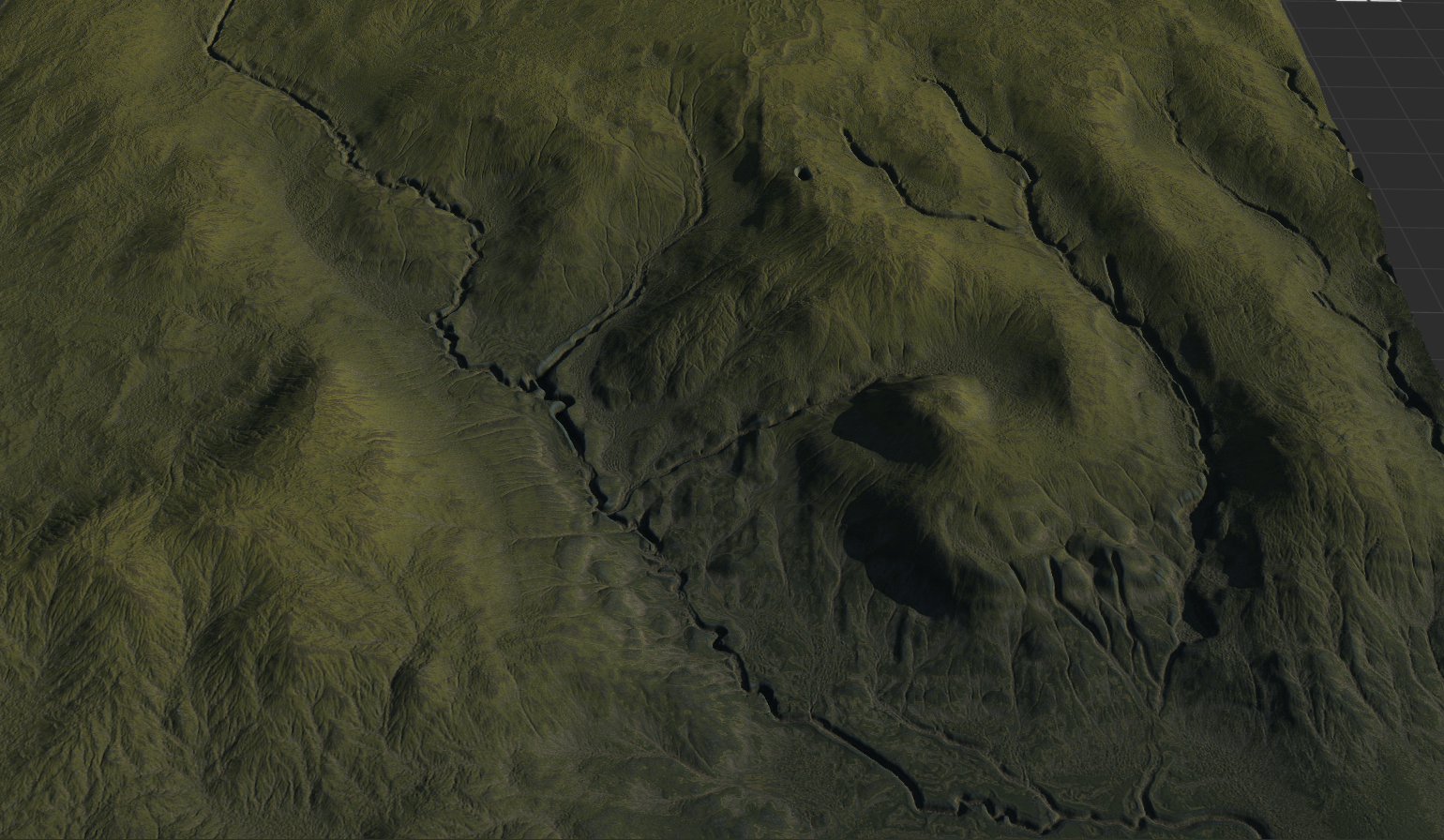

El-hibeh: Reconstructing the Past in Virtual Reality, Master’s Research Project

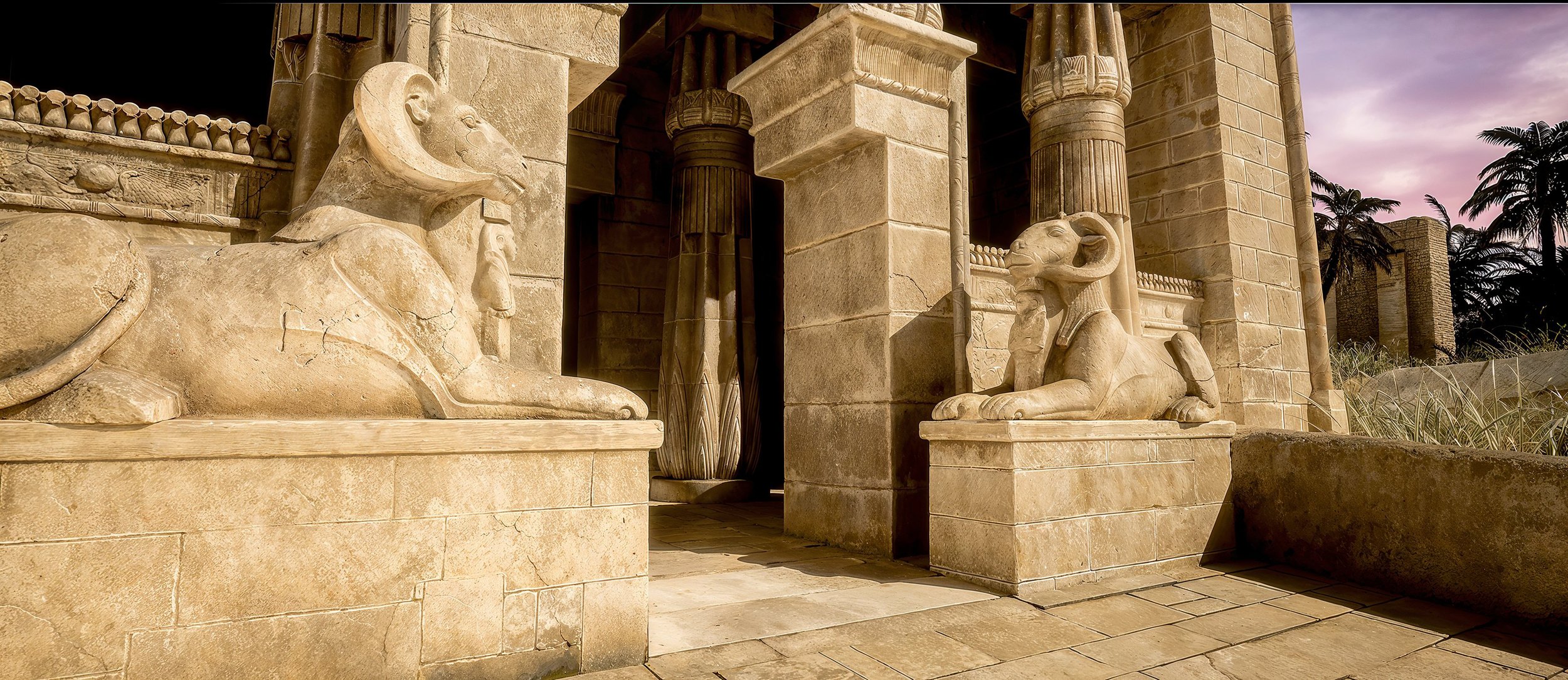

This project was a collaborative venture between UC Berkeley and Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) that focused on reconstructing the Temple of Amun (God of Roaring) in El-Hibeh, Egypt. This 3D model and its surrounding area were realized as a virtual reality experience, connecting the present to the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-664 BCE) when the temple was constructed. You can read my full paper here, or more about the process on my para data blog.

Abstract:

There is a desire to push for innovation in archaeology. Technologies like photogrammetry, point cloud scans, and additive printing are being utilized to document historical sites and catalog entire museum collections. The breadth of my research focuses on how Virtual Reality can preserve the past and build new knowledge for our future. During this examination, questions arise around an object’s authenticity, such as Aura, and whether or not this is a transferable attribute from something with materiality to something with no physicality, such as a digital reconstruction.

Background and Development:

Historical Context:

El-Hibeh, situated 150 km south of Cairo along the east bank of the Nile River, was first developed under Pinodjem I in the Third Intermediate Period as a secondary residence for the Theban rulers. The town transitioned from a large settlement to a fortified temple town, with the Temple of Amun Great of Roaring being constructed under Sheshonq I (945-924 BCE). This temple, smaller than its counterparts at Karnak and Dendera, was architecturally significant, being the first to feature a screened pronaos and a freestanding sanctuary.

Digital Tools and Methodology:

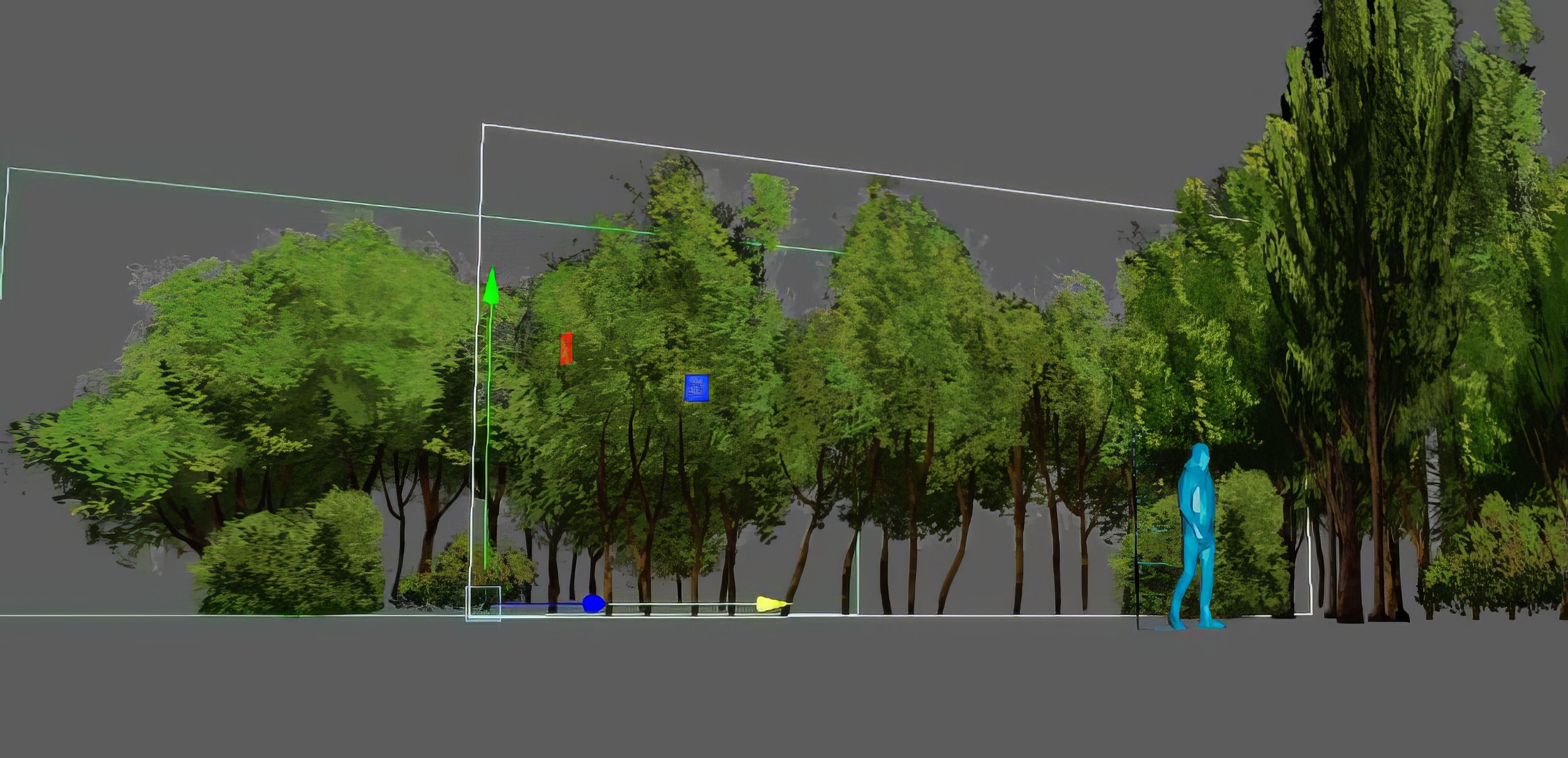

The modelling process utilized several digital tools. Autodesk Maya was used for initial modeling, with organic forms such as statues being detailed in ZBrush. Texturing was done primarily using Substance Painter, which allowed for efficient file management by packing roughness, metallic, and occlusion data into a single file. The Unreal Engine was chosen for the VR environment due to its superior lighting and rendering capabilities compared to other options like Unity.

Construction Phases:

The reconstruction involved two main phases:

Initial Phase: Preliminary construction began in March 2017, using Hermann Ranke's early 20th-century illustrations as a guide. The first version of the temple had several inaccuracies due to my initial lack of detailed knowledge of Egyptian architecture. Issues such as improperly positioned ceilings and misplaced screen structures required a complete rebuild.

Final Phase: The final model incorporated feedback and additional research, resulting in a more accurate reconstruction. This version included detailed textures, realistic lighting, and digital avatars to provide a sense of scale and enhance the immersive experience.

Digital Avatars and User Experience:

To address the sense of emptiness in the VR environment, digital avatars representing ancient Egyptians were introduced. These avatars, initially designed as simple cardboard cutouts, evolved into more complex models. However, challenges such as the uncanny valley effect and lighting issues that altered the perceived skin color of the avatars highlighted the need for careful consideration in their design and implementation.

Presentations and Reflections:

Presentations:

The VR walkthrough was presented at several academic conferences, including:

2017 SSEA Scholars' Colloquium, University of Toronto

2017 Ontario Archaeological Society - Virtual Archaeology and Meaning-Making: Aura and Presence through Virtual Reality, Ryerson University

The project demonstrated the potential of VR as a tool for archaeological interpretation, offering users a unique way to engage with and understand ancient environments. Including digital avatars and interactive elements provided a more immersive experience, though it also introduced new challenges related to the authenticity and representation of historical figures. Future work will address these challenges by incorporating more detailed environmental elements and enhancing the interactivity of the VR experience. Continued research and development in this field will further enhance the accuracy and immersion of such digital reconstructions, offering new insights into historical sites and cultures.

Digital Other: The Creative Use of Digital Avatars in Virtual Reconstructions, Presentation, University of Tubingen, Germany, 2018

I was privileged to present my research at the 2018 CAA (https://2018.caaconference.org/ ) conference in Tübingen, Germany, supported by a Conference Scholarship from Sheridan College. This presentation, titled "Digital Other: The Creative Use of Digital Avatars in Virtual Reconstructions," allowed me to share insights from my project on the virtual reconstruction of the Temple of Amun at El-Hibeh, Egypt. It was my first international presentation and a fantastic experience overall. Here is a pdf of my presentation: Digital Other: The Creative Use of Digital Avatars in Virtual Reconstructions

Abstract: As virtual reconstructions of archaeological landscapes have become more pervasive, it has become clear that the virtual experience has a haunted emptiness. Although highly charged in the representation of the “other,” digital avatars that represent ancient inhabitants of these landscapes, we endeavour to envision help to ground and situate the virtual archaeological interpretation and our understanding of how these landscapes might have been inhabited. Digital avatars became a digital extension of dioramas being used worldwide, such as those found at the Museum of Natural History in the Spitzer Hall of Human Origins or Sterling Castle in Scotland, effectively illustrating characters frozen within life moments. As part of recent research into the virtual (re)imagination of the ancient Middle Egyptian temple of Amun Great of Roaring at el-Hibeh, Egypt, I explored how a digital environment with this visual representation of ancient characters and content could be pushed further. How would adding higher fidelity, lifelike avatars affect the virtual experience? Should these characters move and interact with objects in the environment or even acknowledge a viewer’s presence? How could advances in AI be utilized for these virtual humans, and should they? To create a more extraordinary phenomenological experience, could these avatars be more than static video game characters? Through users’ engagement, I explore this creative disruption with a jarring effect, suggesting that avatars enhance and distract from the reconstructed archaeological landscape.

Detailed Insights and Additional Information:

Addressing the Emptiness:

During the initial stages of the VR reconstruction, the focus was on accurately depicting the architectural and environmental details of the temple. This phase involved extensive research into Egyptian architecture, art, and culture to create a faithful representation of the Temple of Amun. However, as the temple approached completion, it became apparent that the virtual environment felt empty and lacked a sense of lived-in realism.

To address this, I incorporated placed objects within the temple, similar to those found in dioramas, to enhance the phenomenological experience. However, these static objects alone were not enough to fill the void. The next step was to introduce digital avatars to give viewers a sense of spatial awareness and human presence. Initial versions of these avatars were simple cardboard cutouts, but this raised questions about how realistic and interactive these digital humans should be.

Exploring Realism:

Inspired by stylized store mannequins and museum dioramas, I experimented with various forms and colours to avoid uncanny valley effects while maintaining interest and narrative. The avatars were designed and stylized to add interest without distracting from the surrounding environment.

Feedback and Adjustments:

Attendees highlighted the importance of collaborating with experts in anthropology, digital humanities, and computer science to enhance the accuracy and interactivity of digital avatars. They suggested forming partnerships with specialists who could provide deeper insights into the cultural and social aspects of the ancient inhabitants. One idea was to scan people from today; however, diets and lifestyles have changed significantly and would not accurately capture the essence of these ancient peoples.

Several scholars emphasized the need for careful cultural representation. They recommended engaging with communities and descendants of ancient Egyptian populations to ensure that the avatars' design and behaviour are respectful and accurate. It was stressed that when necessary, the people being represented should be the ones creating the avatars to add a greater sense of authenticity. This approach is further explored in a later research project, Longhouse 5.0.

Longhouse 4.0

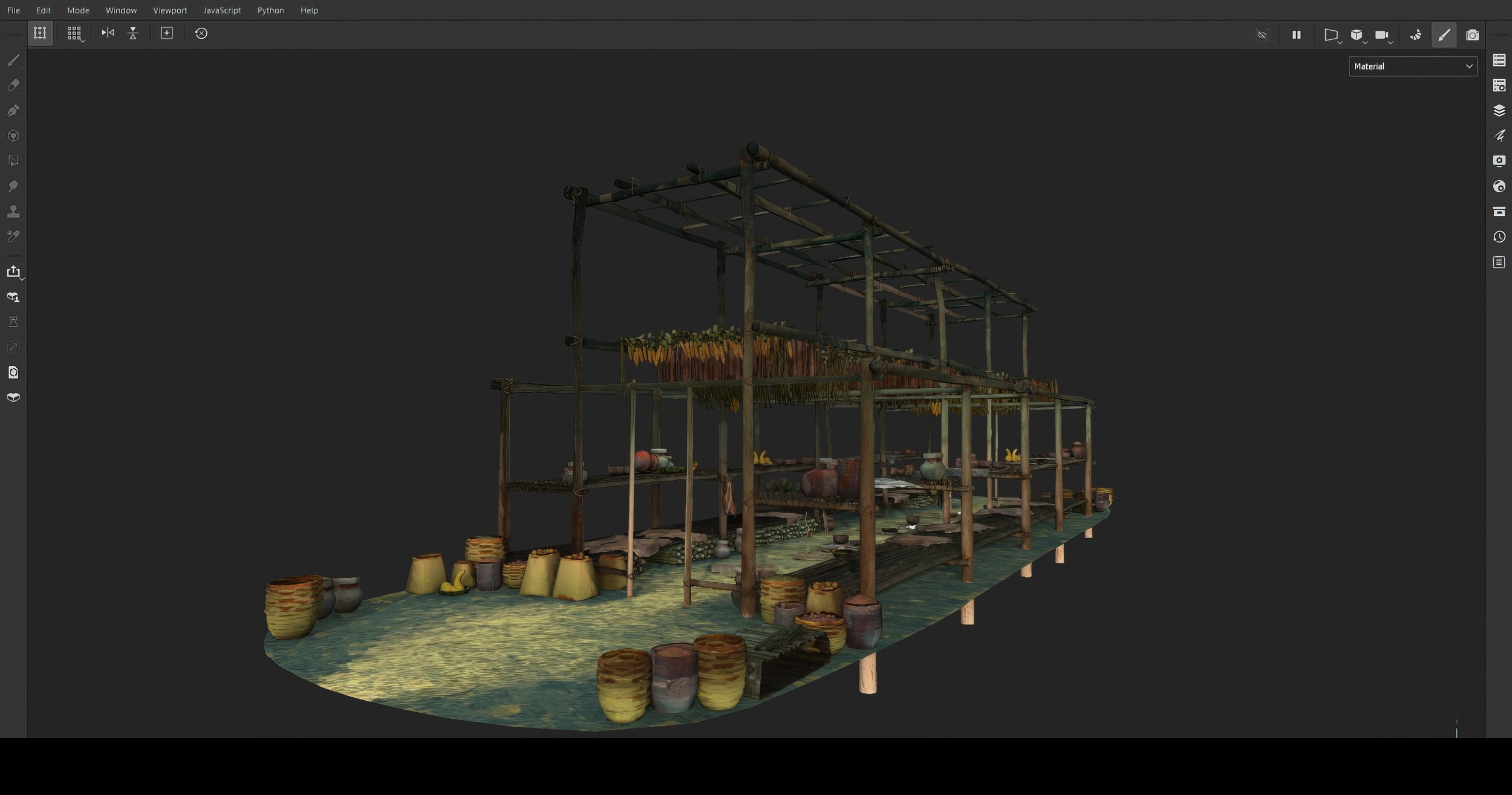

Longhouse 4.0, Co-investigator

In 2019, I had the opportunity to continue the development of an existing VR Longhouse project, initially led by Dr. Michael Carter. This project, known as Longhouse 4.0, was prominently displayed at the Whitchurch-Stouffville Museum & Community Centre. The Mantle Site, which the project is based on, is the largest and most complex ancestral Wendat-Huron village excavated in the Lower Great Lakes region, representing nearly 100 longhouses in a massive pre-European contact city.

This project received support from multiple organizations, including Nation Huronne-Wendat, the Town of Whitchurch-Stouffville, ASI | Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Services, Museum of Ontario Archaeology, and theskonkworks incorporated.

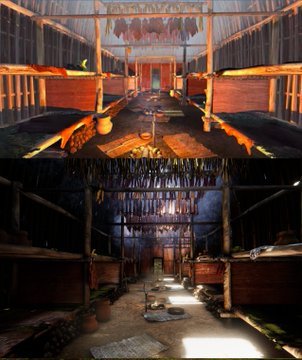

The initial vision for this new iteration was to create a multi-structure environment demonstrating the scope of these settlements. However, due to certain constraints, the direction shifted towards updating the look and feel of the previous version, Longhouse 3.0, built by CG veteran Craig Barr. While impressive for its time, the technology available in 2015 limited the polycount, texture resolution, and lighting capabilities.

My goal for Longhouse 4.0 was to add an extra level of realism by focusing on advanced lighting techniques, material interaction, and the introduction of global illumination to simulate realistic light bounces within the structure’s interior.

Lighting and Texture Enhancements: My primary focus was to enhance the environment through advanced lighting techniques, material interaction, and the introduction of global illumination to simulate realistic light bounces within the structure’s interior. This approach aimed to create a more immersive and lifelike representation of the longhouse environment.

Project Highlights

Lighting and Texture Enhancements: My primary focus was to enhance the environment through advanced lighting techniques, material interaction, and the introduction of global illumination to simulate realistic light bounces within the structure’s interior. This approach aimed to create a more immersive and lifelike representation of the longhouse environment.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: The project involved collaboration with experts in various fields, including 3D Animation and Gaming, Architecture, Sound Design, UX/UI Design, Anthropology, and Archaeology, to ensure historical accuracy and cultural sensitivity. By combining archaeological data with creative speculation, we produced a rich and engaging experience.

Materiality: Emphasizing the materiality of the digital reconstruction was key to creating a tangible and authentic experience. By carefully simulating the textures and physical properties of materials such as wood, stone, and organic matter, we aimed to bridge the gap between the virtual and the physical, enhancing the viewer’s connection to the reconstructed space.

Sensory Experience: The environment included simulated artifacts and traditional elements like sweetgrass and other indigenous herbs to provide an authentic experience. This helped to create a sensory-rich environment where users could engage with the sights and sounds of a traditional longhouse.

The exhibition The Longhouse 4.0 project is displayed at the Whitchurch-Stouffville Museum & Community Centre. TMU's architecture students built and assembled the enclosure for the exhibit, contributing significantly to its overall presentation. This project not only updated the visual and technical aspects of the previous version but also set a foundation for future developments in digital heritage preservation.

The project has also been featured on signage for the Museum of Ontario Archaeology in London, Ontario, and on the cover of "Virtual Heritage: A Guide," edited by Erik Malcolm Champion.

Sheridan Insider wrote a small article with more details: https://www.sheridancollege.ca/newsroom/news-releases/2019/07/sheridan-professor-helps-recreate-digital-iroquoian-longhouse-for-local-museum

Longhouse 5.0

Longhouse 5.0, Co-investigator, 2021

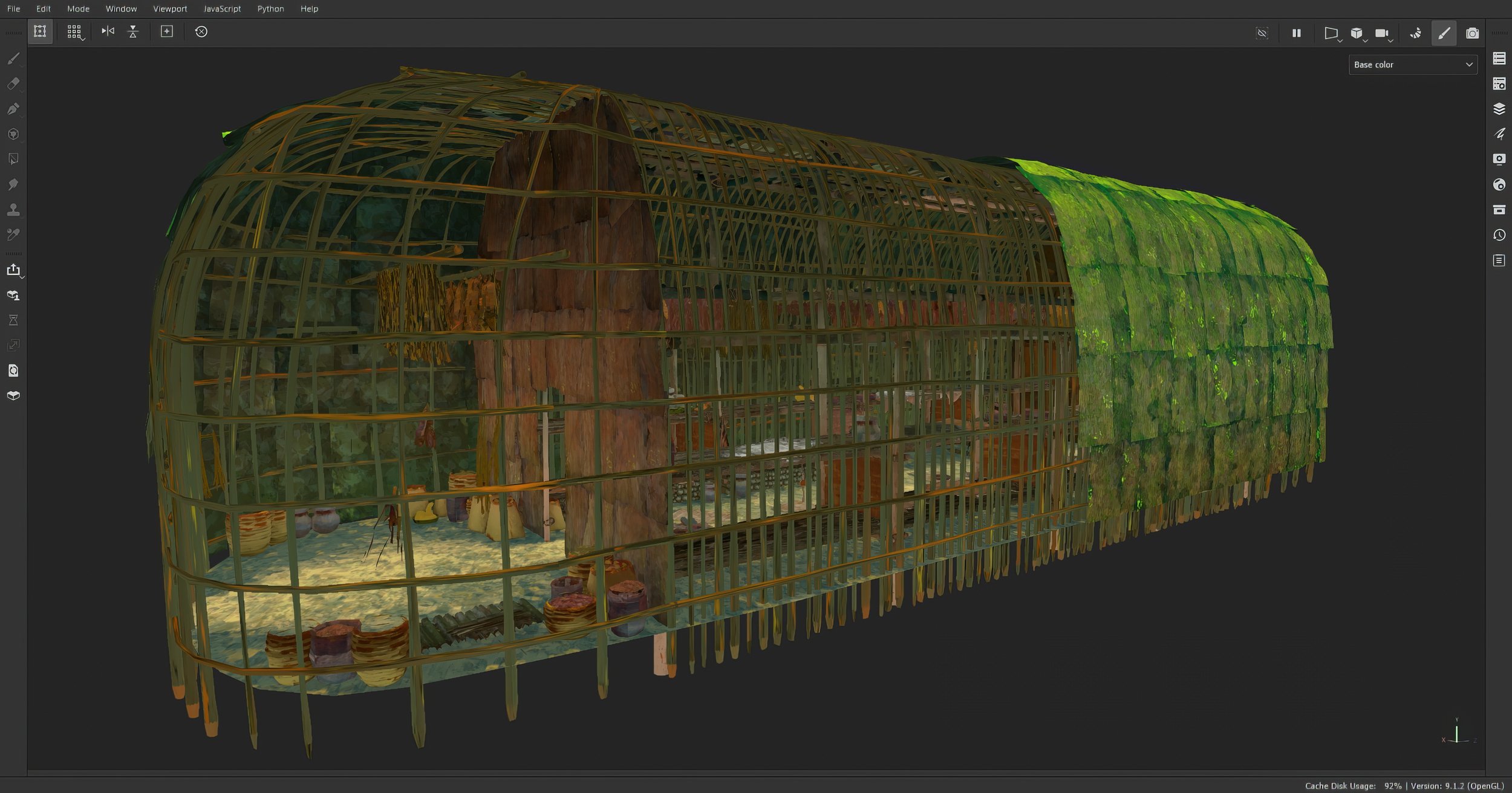

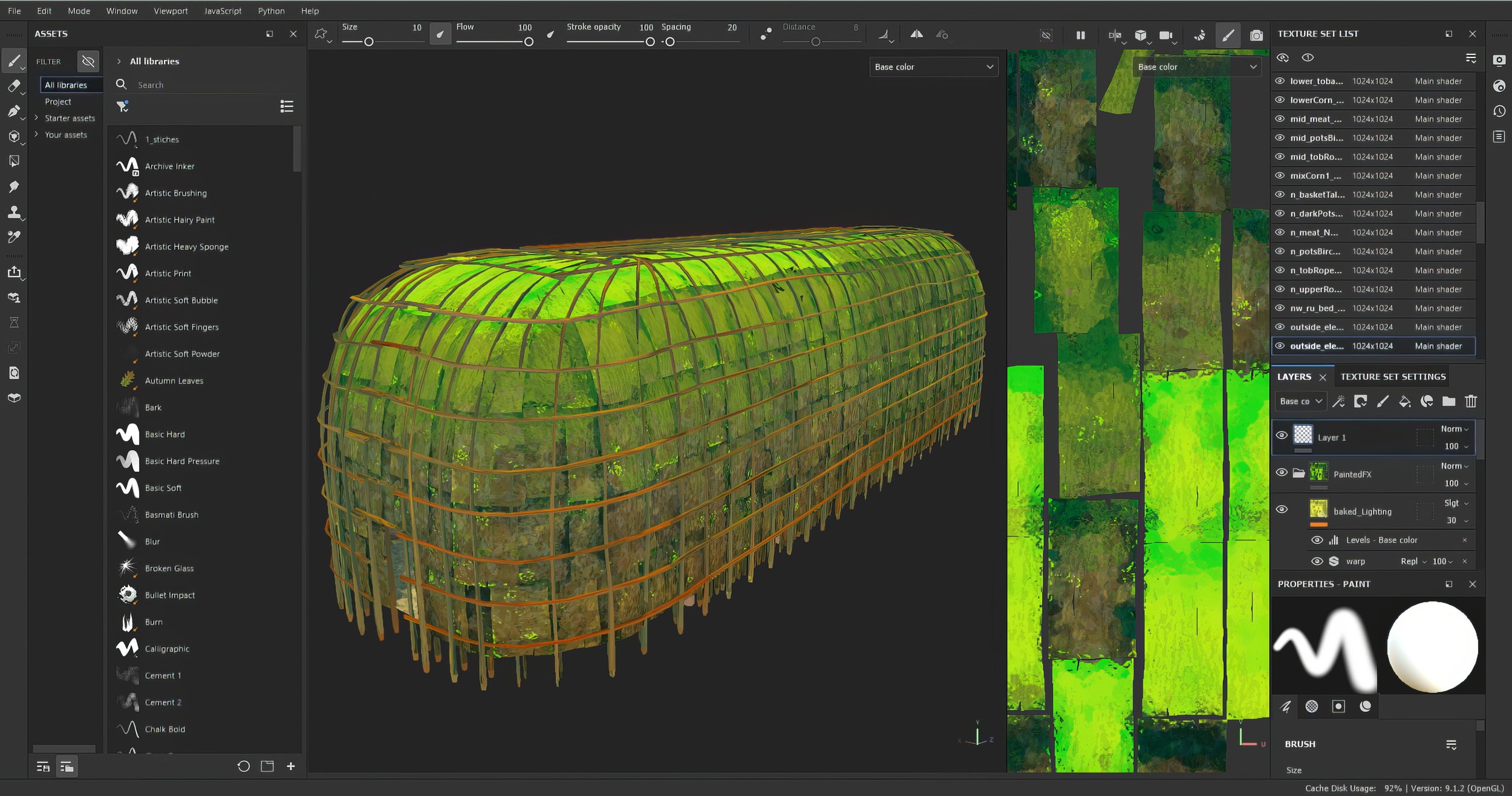

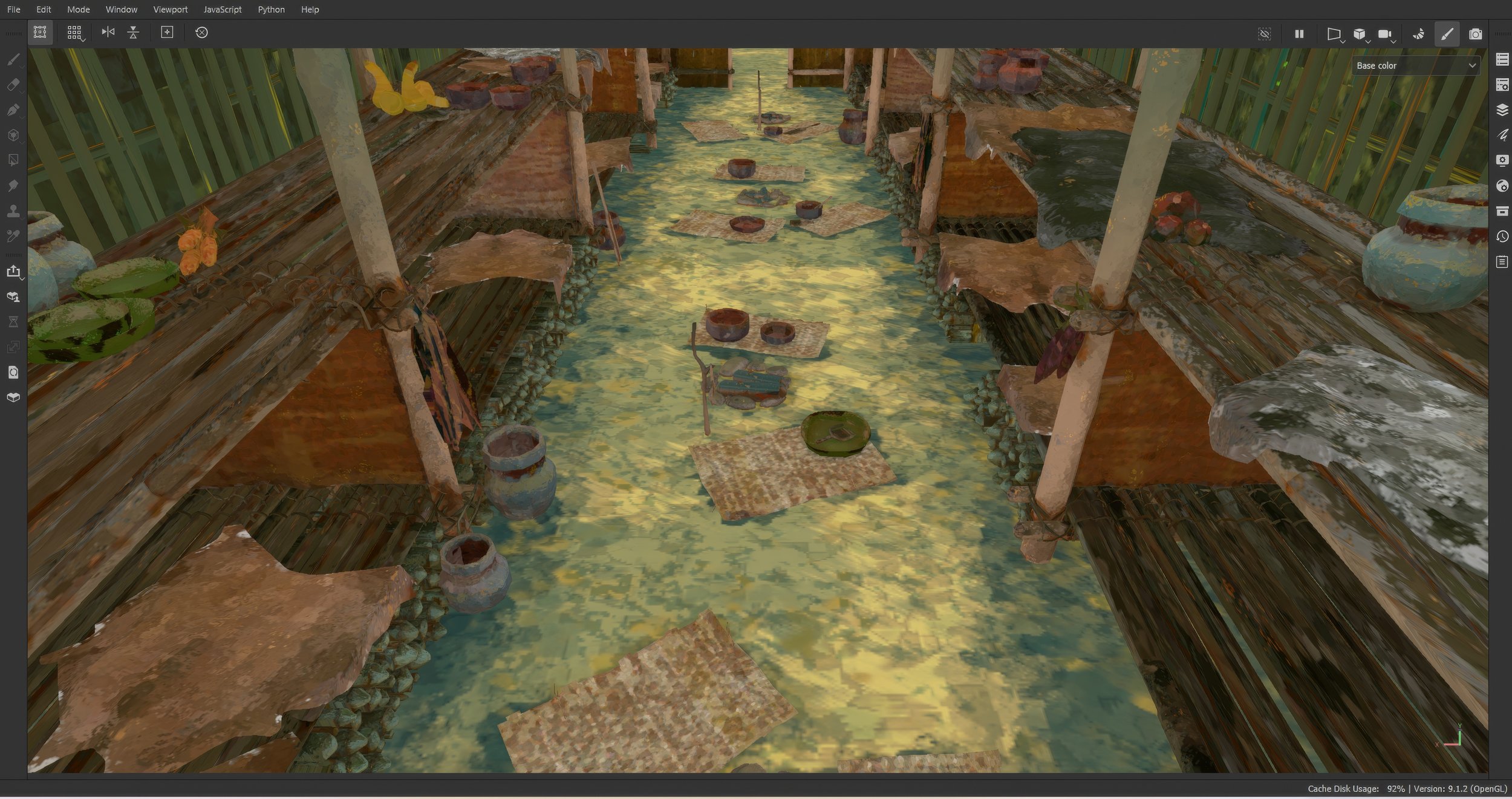

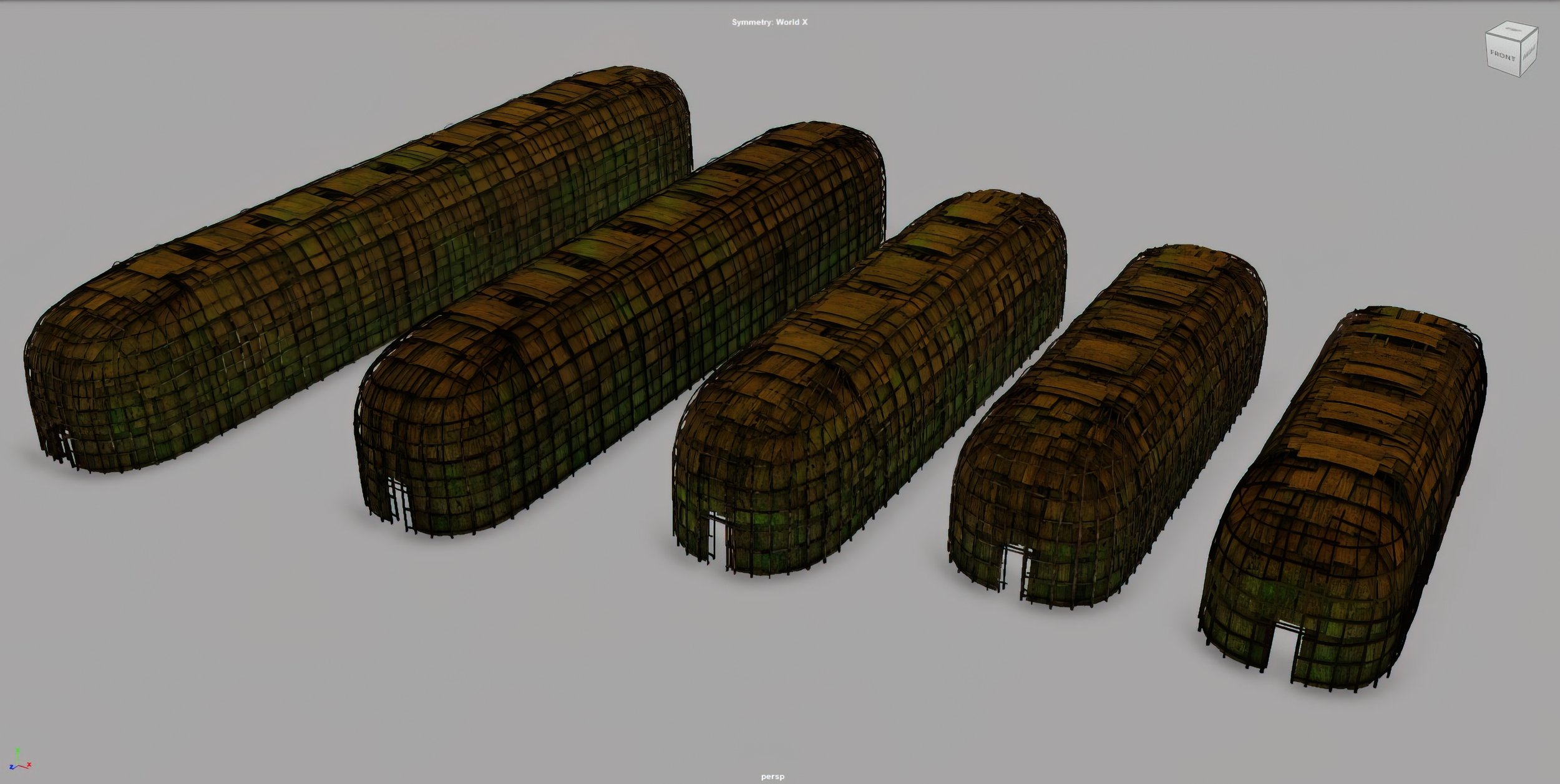

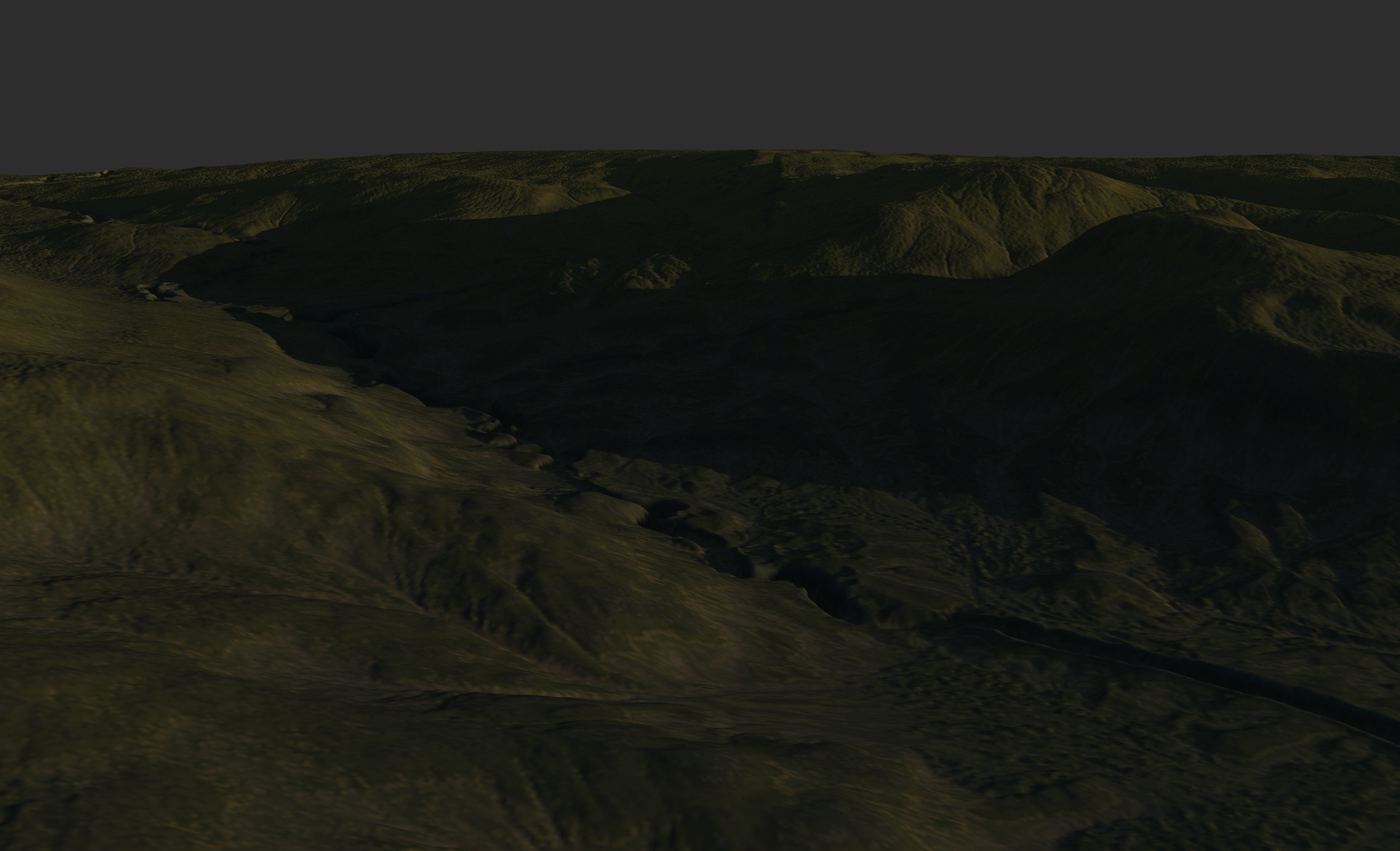

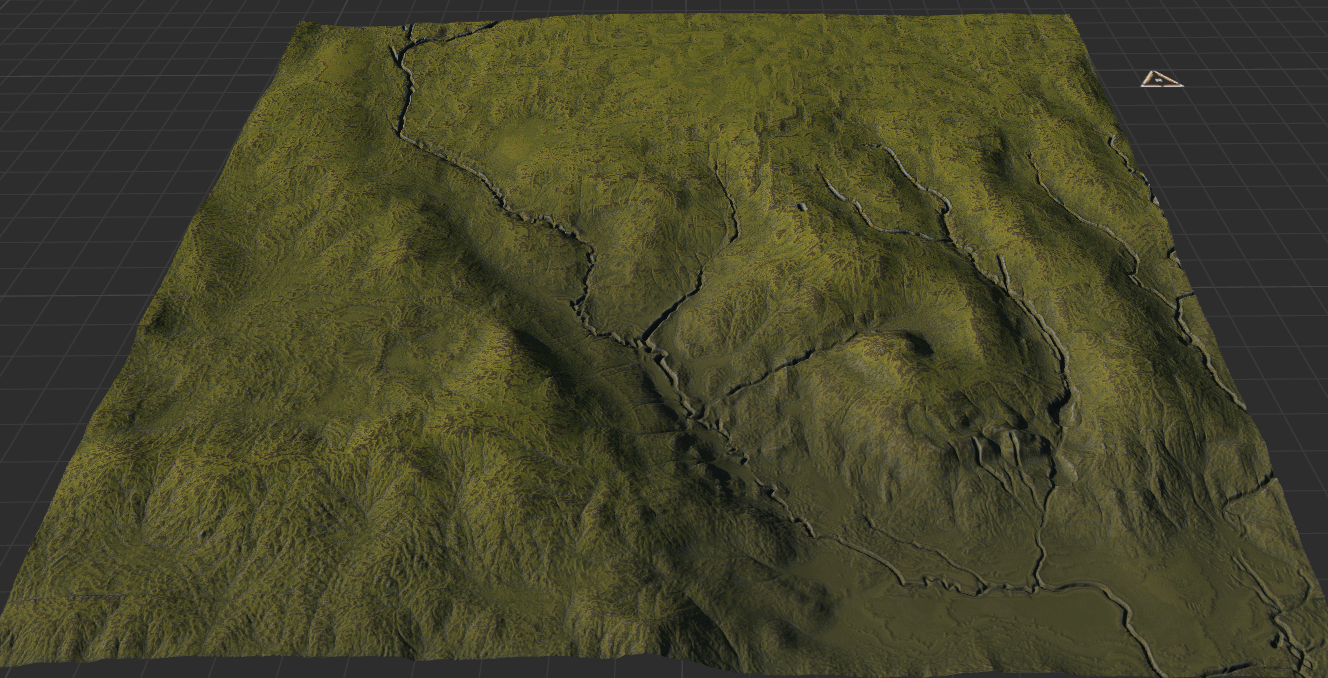

This new version of the longhouse was led by Namir Ahmed from Toronto Metropolitan University. Longhouse 5.0 aimed to realize all the aspects we couldn’t incorporate into 4.0, with significant advancements in both scope and detail. In collaboration with the Huron-Wendat community, the concept for this new visualization addressed three iterations of village lifecycles: past, present, and future. A typical village would be utilized for around 30 years before the surrounding resources would be diminished. With this in mind, a viewer could begin in a vibrant mid-lifecycle village, travel to a village abandoned and in a state of decay, and then progress to a new village site where construction was just beginning. All three iterations were pre-contact, providing a comprehensive view of the Huron-Wendat's dynamic settlement patterns.

The Sheridan team modelled various objects essential to depicting daily life and activities. This included fishing tools, weapons, pottery, and housing structures. The team conducted extensive research and consultation with historical records and the Huron-Wendat community to ensure these models' accuracy and cultural sensitivity. For instance, the fishing tools included spears and nets, vital for subsistence along the waterways. Transportation on the water was also important. Canoes were crafted from birch bark and framed with wooden ribs, while paddles featured intricate carvings.

One of the significant advancements in Longhouse 5.0 was the inclusion and representation of the village’s inhabitants. Feedback from previous versions indicated that the lack of people was somewhat unsettling. This ties into my earlier research from the El-Hibeh temple reconstruction, where the absence of inhabitants left the environment feeling empty. In version 4.0, audio was added to infer that the area was populated, with sounds like people conversing, children playing, fire crackling, wind, and running water. For 5.0, we aimed to authentically represent the indigenous groups through digital avatars. Initially, we explored using Epic Games' Metahuman tools, allowing the indigenous population to craft their avatars. This software is free and accessible online, making it an excellent option for creating realistic and editable characters that could be fully rigged and animated in the Unreal Engine. However, we later partnered with Awastoki, a Huron-Wendat-owned and operated collective of CG artists, which aligned better with our goals for authenticity and cultural representation.

Awastoki brought a deep understanding of cultural nuances and artistic traditions. They created lifelike digital avatars, accurately representing the Huron-Wendat people. Their work included detailed modelling of traditional clothing, hairstyles, and body adornments based on historical and ethnographic research. Awastoki also guided the animation of the avatars to reflect traditional movements and gestures. We hoped to collaborate with Sheridan’s SIRT to motion capture Indigenous actors performing daily village tasks. Unfortunately, this didn’t work out within our schedule and time constraints.

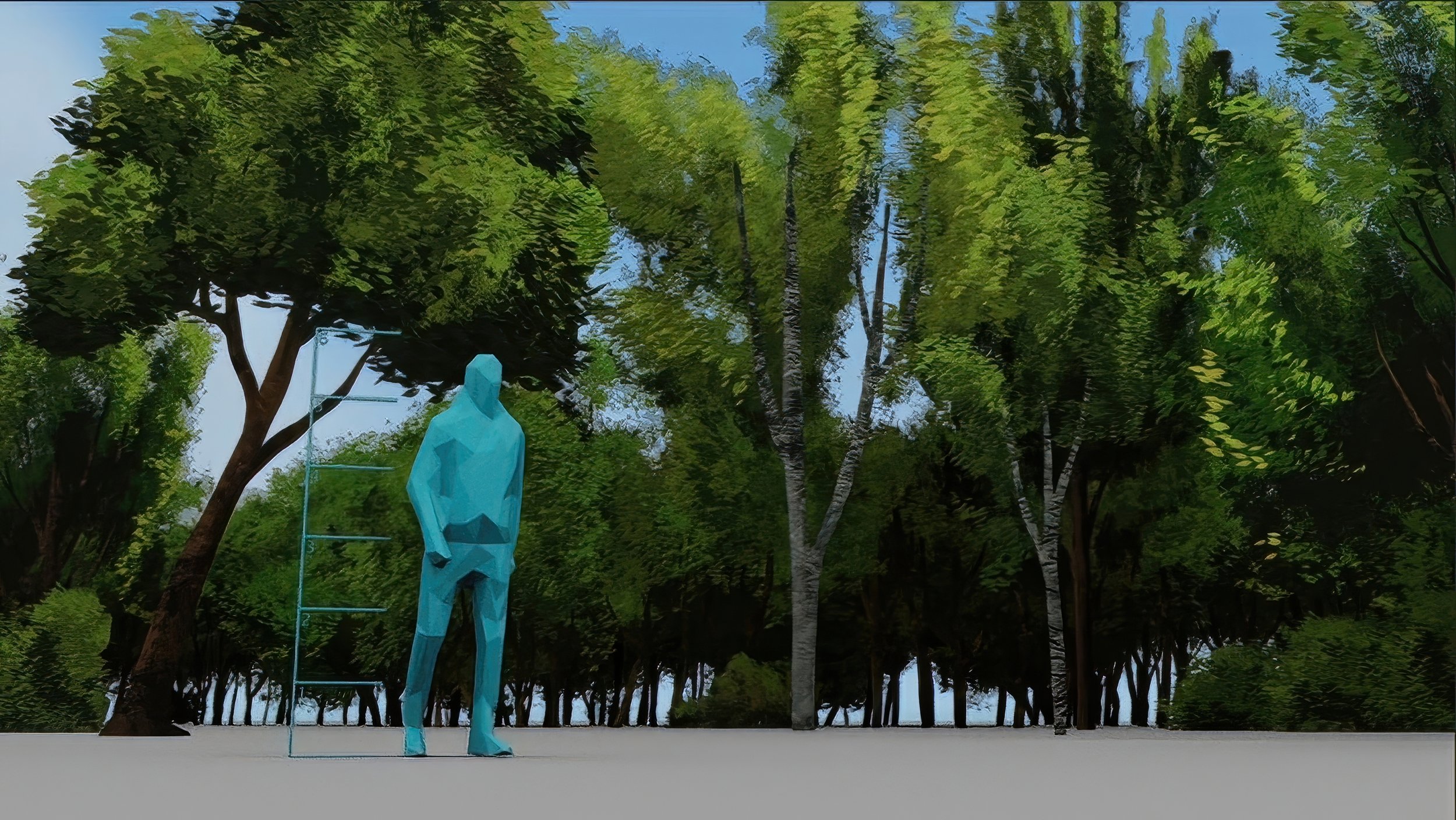

Technological constraints also influenced our approach. We adopted a more illustrative look for the project to address the limitations of mobile VR platforms. This artistic direction helped to balance the need for detailed, immersive environments with the processing capabilities of the devices, ensuring a smooth user experience. The style was inspired by the painterly look found in Studio Ghibli movies, such as "Spirited Away," which allowed for impressionistic elements while maintaining a level of materiality found in real objects.

The development process involved significant experimentation and iteration. Initially, we simplified the number of objects by combining similar geometry and then laid out their new UVs. Once we had fewer polygon objects, we projected the original textures onto the updated UV layouts. We used procedural texture editing software like Substance Painter and Substance Alchemist to add wear and tear and enhance the materials' natural feel. This process allowed us to create high-resolution textures while optimizing the models for VR.

Several architectural insights were gained during the building process:

Discussions between archaeologists and architects raised multiple questions about the construction and assembly of the longhouse structure. The research gathered from archaeologists was presented to the research team, including architectural science professor Vincent Hui. This dialogue highlighted procedural discrepancies and speculations on how the construction might have been executed, drawing parallels with modern practices.

One significant finding was that the longhouse structure resembled the hierarchical structure of modern office towers. The interior framework of the longhouse acted as a core structure, while the outer cages and bark shingles functioned like a curtain wall system to shed water, withstand wind loads, and contain heat. This understanding emphasized that the internal framework was the primary structural element.

Another key finding concerned the cedar bark shingles' envelope structure layered on the wall system. Archaeological evidence indicated a secondary cage structure imposed on the initial envelope for repair and reinforcement as the longhouse aged. This suggests that the initial structure was built solely with cedar bark, and over time, a layered and heavier envelope developed, raising questions about longhouse maintenance and the individuals responsible for it.

A third finding related to the depth of the cage structure in the ground. Recorded at 40 cm below grade, it did not reach the 1.2 m frost line in Ontario, raising concerns about how the longhouse's shape and structure would distort over time due to ice lensing and frost heaving. The archaeological evidence suggests the construction was resilient, accommodating the same forces we manage today.

This project was funded by an eCampusOntario grant, supporting the integration of Indigenous practices and education into the curriculum. The core development team included CG artists from Sheridan College, researchers from Toronto Metropolitan University, and Huron-Wendat historians, ensuring a comprehensive and culturally accurate representation. By collaborating closely with the Huron-Wendat community and utilizing advanced digital tools, Longhouse 5.0 provided an engaging educational tool that brought the history and culture of the Huron-Wendat people to life.

Longhouse 5.0: A Simulation of Indigenous Construction and Life in the 14th Century, Presentation, Macquarie University, Australia, 2021

This virtual educational talk was for the Living Digital Heritage 2021 Conference (LDH21), Centre for Ancient Cultural Heritage & Environment. The focus of our presentation was around the current development of Longhouse 5.0.

Abstract: As part of an ongoing investigation, consultation, and education process, Canada is coming to terms with its treatment of its indigenous population. As part of this response, Ontario Universities are implementing indigenous practices and education as a core component of the curriculum through various strategies. In this paper, we describe one such approach. In partnership with the Faculty of Architecture and the Huron-Wendat nation, a VR simulation of prehistoric (pre-1550) Southern Ontario is in development to allow students and faculty the ability to explore an Indigenous Huron-Wendat city through the lens of cultural practices and building construction methodology. The core development team is experienced in both cultural resource management and media production. We employ these competencies throughout each stage of the project. Here, we describe the development process and decisions made while engaging stakeholders and industry professionals. We express our use of Unreal’s Metahuman and cultural sensitivities that must be considered. We describe game design decisions and narratives while incorporating the needs of our Indigenous collaborators. The process of development for effective and engaging digital media is challenging. We summarize with ‘lessons learned, recommendations for other such projects, and our understanding of best practices gained.

During the Living Digital Heritage 2021 Conference at Macquarie University, we focused on the latest developments in Longhouse 5.0. The project addresses the challenge of representing indigenous cultures authentically in a digital format. A significant advancement in Longhouse 5.0 is the inclusion of digital avatars created in collaboration with Awastoki, a Huron-Wendat CG house, ensuring cultural accuracy and community representation. This addition resolved the previous version's criticism of feeling static and empty, providing a more dynamic and interactive environment. We also discussed the development of the avatars and how we initially looked to Metahuman, released by Epic Games (https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/digital-humans?sessionInvalidated=true), to build and animate secondary and background characters. This led us to partner with Awastoki, who created the inhabitants incredibly.

Longhouse 5.0: A 3D Recreation, Cabane d'automne 11e, Forêt Montmorency, Wendake, 2022

I was fortunate to have been invited to Wendake with Lead Investigator Namir Ahmed (Toronto Metropolitan University) to present Longhouse 5.0 at the annual Cabane D'automne. Version 5.0 continued Michael Carter's Ph.D. work and expanded the Longhouse project's scope to encompass an entire Huran-Wendat village, including its inhabitants and surrounding agricultural lands. The recreation is based on the Mantel Site (also called Jean-Baptiste Lainé) in Whitchurch-Stouffville, Ontario.

The two-hour presentation was divided into four sections:

Jean-Phillipe Thivierge (Bureau du Nionwentsïo) oversaw the project's historical research and cultural guidance and contextualized the Longhouse's history.

Caroline Fournier and Alexis Gros-Louis Houle (Awastoki) explained the process of creating the Avatars that populated the village.

Namir and I explained the development process.

And we wrapped up with a live demonstration.

After the talk, multi-generational participants from Wendake tried out the experience with the Oculus Quest2. The fact that the project received such a positive response and the realization that this could potentially be an expandable educational tool was incredibly gratifying.

I was able to walk through a real recreation of a longhouse and palisade beside the Wendake Museum.

Jean-Phillipe Thivierge, Me, Namir Ahmed, Caroline Fournier, and Alexis Gros-Louis Houle

Some of the Wendake participants experiencing the Longhouse 5 recreation.

Visualizing the Indigenous Architectural Past through Virtual Reality & Gaming (2025)

Published in: Architecture and Videogames: Intersecting Worlds (Routledge, 2025)

Co-authors: Kristian Howald, Namir Ahmed, Dr. William Michael Carter

This research explores the challenges and methodologies involved in digitally reconstructing Jean-Baptiste Lainé, a 14th-century pre-contact Huron-Wendat city, using VR and gaming technologies as tools for community engagement and heritage preservation. This work builds upon my Longhouse 5.0 research, extending discussions on authenticity, digital reconstruction, and indigenous storytelling in virtual spaces.

"How do consumers differentiate between constructed and known historical knowledge when experiencing virtual worlds in an ever-increasing hyper-realistic digital media environment? Specifically, how does one visualize built heritage if significant gaps exist in the archaeological and historical record?"

📖 Read more on Routledge

It was an honour to have my work on the longhouse project and the chapter "Visualizing the Indigenous Architectural Past through Virtual Reality and Gaming" acknowledged by my colleague, Vincent Hui. This chapter, part of Videogames and Architecture | Intersecting Worlds, explores how virtual reality and gaming can be used to reconstruct and engage with Indigenous architectural heritage.

The recognition highlighted the challenges of visualizing built heritage when gaps exist in historical records, emphasizing the importance of cultural sensitivity and collaboration. I’m especially proud that this work bridges technology with storytelling, providing new ways to understand historical narratives while inspiring future innovation in architecture and digital heritage.

Exhibition Feature: Energy-Efficient Indigenous Architecture, Madrid, Spain (2025)

A rendered image from Longhouse 5.0, originally shared via the open-access repository supported by our eCampusOntario grant (link), was selected and engraved onto wood panels for public exhibition in Madrid. Curated by architect María Jesús Montero, the event focused on sustainable Indigenous design. This marks the second time the Longhouse project has been featured by a European architect and highlights the international impact and accessibility of our digital heritage research.